The Human Imprint: How Our Choices Are Reshaping the Climate

- Aditi Joshi

- Sep 4, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Oct 11, 2025

For centuries, Earth’s climate has shifted through cycles of ice ages, monsoon variations, and long-term oscillations driven by forces far beyond human influence. But in the past two hundred years, something different has taken hold. The scale and speed of change today cannot be explained by natural variability alone. Human activity - from the burning of fossil fuels to the clearing of forests - has become the defining driver of global climate disruption.

This recognition is not about assigning blame but about confronting reality. Understanding that the climate crisis is rooted in human systems gives us both clarity and agency. It means that the pathways that led us here were not inevitable, and that the road ahead can still be altered by choices we make now.

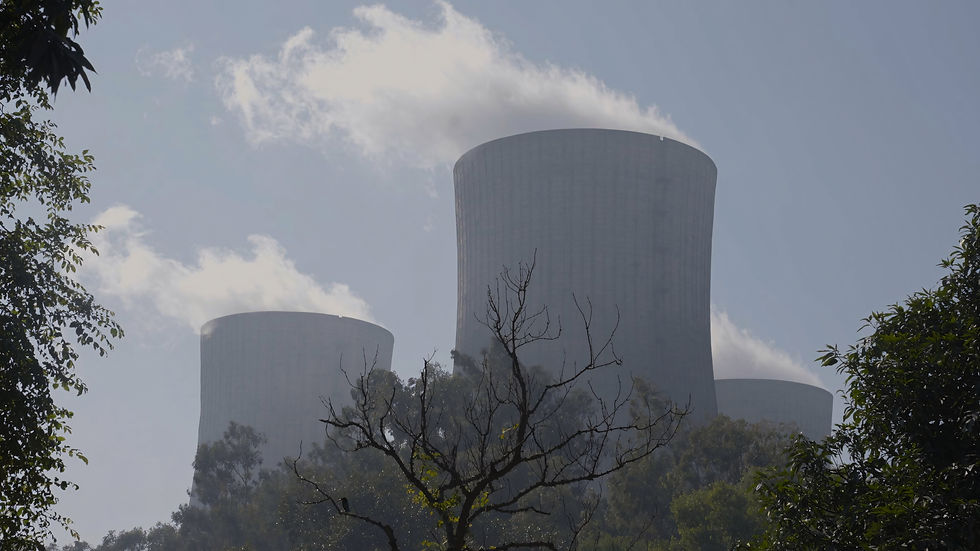

Industrialization and the Carbon Legacy

The Industrial Revolution was more than a turning point in history; it was the beginning of an entirely new relationship between humans and the atmosphere. Coal-powered factories lifted millions out of poverty and accelerated technological change, reshaping societies across continents. Yet the same chimneys that symbolized progress were releasing gases that would accumulate invisibly, altering the planet’s energy balance.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) - the principal greenhouse gas - rose from 280 ppm in pre-industrial times to over 420 ppm today, the highest concentration in hundreds of thousands of years. Unlike the smoke that quickly dissipated from factory stacks, CO₂ remains in the atmosphere for centuries. Every tonne emitted leaves a trace that compounds over time.

Even now, more than two centuries later, coal, oil, and natural gas remain the foundation of modern economies. They power industries, heat homes, move vehicles, and enable global supply chains. This continuity illustrates both the achievements and the costs of industrialization. The very systems that made societies more prosperous also made them more dependent on fuels that destabilize the climate.

Forests and the Decline of Natural Balances

If smokestacks represent one side of human influence, deforestation represents another. Forests serve as the planet’s lungs, absorbing carbon and regulating rainfall patterns. But global demand for land and resources has driven their steady decline.

Since 1990, the global forest area has shrunk by approximately 420 million hectares - an expanse nearly equal to the European Union - primarily due to conversion for agriculture and other land uses. During the most recent five-year period (2015-2020), the average annual deforestation rate remained high at 10 million hectares, despite a declining trend from earlier decades. Commercial agriculture, especially cattle ranching, soy, and palm oil production, accounted for roughly 40% of tropical deforestation between 2000 and 2010, with an additional 33% linked to subsistence farming. These land conversions feed into international markets, making the drivers of deforestation global rather than local.

The ecological consequences are profound. Deforestation reduces carbon sequestration, accelerates biodiversity loss, and disrupts hydrological cycles. Forests once acted as stabilizers, buffering temperature and rainfall extremes. Their removal destabilizes entire regions, making them more vulnerable to droughts, floods, and heat stress.

Agriculture and the Paradox of Food Production

Agriculture is often framed as the sector most exposed to climate impacts, and rightly so. Shifting monsoons, prolonged droughts, and extreme rainfall events jeopardize harvests across the world. But agriculture is also a contributor to the very crisis it suffers from.

Livestock, particularly cattle, produce methane (CH₄), a greenhouse gas far more potent than CO₂ in the short term.

The use of synthetic fertilizers releases nitrous oxide (N₂O), nearly 300 times more powerful than CO₂ in warming potential.

Large areas of forest and grassland are cleared to produce animal feed rather than food directly consumed by people.

Together, these practices make agriculture responsible for about one-quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions. This paradox is central to the climate challenge: the systems that feed humanity also destabilize the climate that agriculture depends upon.

Greenhouse Gases: A Shifting Atmospheric Balance

At the heart of the crisis is a shift in atmospheric chemistry. Greenhouse gases form a thin but powerful blanket around the Earth, trapping heat that would otherwise escape into space.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is the most abundant, contributing about three-quarters of global emissions.

Methane (CH₄), though less common, exerts a stronger short-term effect and is rising rapidly due to agriculture and fossil fuel extraction.

Nitrous oxide (N₂O), while less discussed, has long-term impacts tied to fertilizer and industrial use.

The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (2023) emphasizes that current concentrations are unprecedented in human history. This altered balance explains why global temperatures are climbing, ice sheets are retreating, and extreme events are intensifying.

The Visible Signs: Ice, Oceans, and Weather

The impacts of these emissions are visible across every continent and ocean. The Arctic is warming nearly four times faster than the global average, reshaping ecosystems and opening previously frozen waters (Arctic Council, 2023). Glaciers from the Himalayas to the Andes are retreating, raising concerns for downstream water supplies and sudden floods.

Sea levels have already risen more than 20 cm since 1900, threatening coastal settlements and megacities. Extreme weather once thought rare is now seasonal: Europe’s record-breaking heatwaves, South Asia’s devastating floods, and North America’s intensifying wildfires all bear the fingerprint of climate change.

These are not isolated incidents but interconnected symptoms of a system under stress. The Earth is no longer in a stable equilibrium; it is moving into new and uncertain territory.

Biodiversity at Risk

The effects of warming extend beyond human systems. Ecosystems across the planet are under strain. Coral reefs bleach during marine heatwaves, losing the biodiversity that supports fisheries and coastal protection. Pollinators decline as shifting temperatures and pesticides alter their habitats.

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services warns that over one million species are at risk of extinction. Each loss weakens the web of life, creating vulnerabilities that ripple through food systems, economies, and cultural traditions.

Human Dimensions of the Crisis

The human consequences of climate change underscore its urgency. Rising food prices linked to crop failures, health crises driven by heatwaves and shifting disease patterns, and displacement of vulnerable communities are no longer projections but lived realities.

Between 2018 and 2023, internal displacement worldwide rose sharply - reaching approximately 46.9 million new internal displacements in 2023 alone. Over half of these movements (26.4 million) were triggered by disasters such as storms, floods, and wildfires, underlining the growing link between environmental hazards and human displacement.

Importantly, those who contribute least to global emissions - low-income nations, indigenous groups, and marginalized communities are often the first and hardest hit. This imbalance makes climate change not only an environmental challenge but also a profound justice issue.

Choices and Pathways Forward

Even if emissions were halted today, the inertia of greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere means that warming will not reverse immediately. Some impacts are locked in. But this does not make mitigation futile. Every increment of avoided warming reduces risks, saves lives, and preserves ecosystems.

Pathways forward are clear:

Accelerating the transition to renewable energy.

Protecting and restoring natural ecosystems.

Reducing food system emissions through efficiency, innovation, and dietary shifts.

Building resilient infrastructure to withstand future extremes.

These steps are not only acts of environmental responsibility but also investments in stability and equity.

A Shared Responsibility and Opportunity

We’ve shaped the climate trajectory. Now, we inherit the chance to redirect it. The choices we make through policy, innovation, conservation, and daily action will determine whether humanity steps back from the edge or crosses it.

This isn’t just science; it’s a responsibility built into our collective story. If we commit to equitable, science-led solutions today, we can still steer toward a stable and just future.

Comments